Santa Rosa First Peoples Community,

Arima, Trinidad & Tobago,

June 16, 2020.

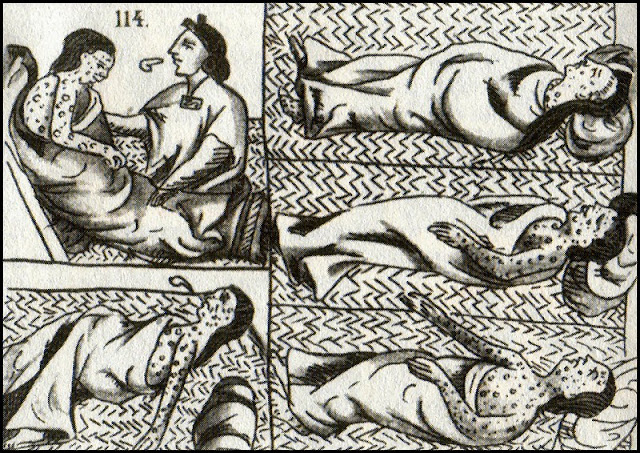

As Amerindians/Indigenous Peoples in the Caribbean, we are historically well acquainted with a series of epidemics and pandemics. We therefore have a lot of historical experience in suffering and surviving from both local epidemics and regional pandemics. We have seen some of the worst in the past, and now the rest of the world is getting a small taste of what we had to go through. The big difference is that we did not have a World Health Organization looking into our situation; nobody came to our assistance; there was no protection or support from the authorities; we were left to our own devices. We have survived the very worst, rebuilt our economies, and we are still here today thanks to our ancestors’ survival skills. We have some lessons to offer from those experiences.

Here are some key points from our historical experience:

(i) “by 1518 only 16,000 [Taino] survived. That year a smallpox epidemic swept through the Spanish colonies, a pandemic, according to the historical demographer Henry Dobyns, that by 1525 had left no American culture untouched. By 1545 the 29 sugar mills on Hispaniola were using nearly 6,000 non-Taino from the South American mainland and the Lesser Antilles and 3,300 Africans as laborers”.i

(ii) In 1739, a smallpox outbreak “decimated” Trinidad’s Indian population.ii

(iii) In 1817 the Yellow Fever Epidemic swept Trinidad, followed by the cholera epidemic in the 1850s; and, smallpox in the 1870s.iii

(iv) “In 1854 a cholera epidemic struck North coast Indians* heavily” (pp. 14–15); “The same epidemic decimated the Amerindian population living in the hills around the old Arima mission”.iv

(v) “On the north coast...the surviving Amerindian families were brought together in the mission at Cumana (Toco); but they disappeared inexorably, and the cholera epidemic of 1854 apparently exterminated nearly all the north coast Indians. By 1885 there were only perhaps a dozen half-caste Amerindian families on the north coast”; “In Arima the story was the same. In 1840 there were only about three hundred Indians of pure descent in the old mission, mostly aged. Occasionally surviving members of a group of Chayma Indians used to come down from the heights beyond Arima to the Farfan estate, to barter wild meats for small household goods. But after 1854 they were seen no more: cholera had extinguished the Chaymas”.v

|

| Chief Ricardo leading his people in prayer |

Part of this pandemic appears to stem from an imbalance between humans and other animals. We cannot afford to continue viewing the natural environment with contempt, or as something to be devoured. The “Medicine Man or Woman” is very important in our culture, with knowledge of the healing herbs and minerals which are gifted to us in the natural environment. The Caribbean Amerindian/Indigenous relationship with the natural, animal world was intensely intimate. It was not just a matter of living in a “harmonious relationship” with nature—it is about being one and the same with nature, inseparable, indivisible, and indistinguishable. On the mainland Amerindian ancestor communities in places such as Guyana, heralded themselves as members of the “Jaguar clan” or the “Eagle clan”—this was not just a matter of empty symbolism. They firmly believed that their ultimate ancestor was a jaguar, or an eagle, and so on. We need to reinstitute that relationship of respect, knowing our limits as human beings, and being attentive to the realities of where we live.

Instead of being constantly and repeatedly exposed to destruction from recurring phenomena, we must learn lessons from the past, and implement changes.

A hurricane will flatten one of our Caribbean neighbours, razing as many as 90% of all structures. So what do they do? They rebuild the same sort of structures that are vulnerable to destruction from hurricanes—square or rectangular houses, with jagged rooftops. The best structure is the Amerindian/Indigenous one, which is conical, and at the very worst is easy to rebuild.

The same is true about having an abundance of root crops (ground provisions), as practised by the Amerindians/Indigenous People. Ground provisions cannot be destroyed in a hurricane, thus ensuring that people have a ready supply of food in order to rebuild.

This pandemic revealed similar frailty. We are fragile by design: it is an outcome of inappropriate policies, and inadequate planning. Our dependency on foreign imports of food placed us in a situation of great insecurity. People were also dependent on going out to buy food, rather than turning to supplies that could have been provided by their own gardens—we were over exposed, and for no good reason.

In rebuilding, there needs to be a dramatic new investment in local agriculture, and a national plan that includes everyone—not just career “farmers”. Every yard needs to be planted. There should be an abundance of cassava flour that renders imported wheat flour too expensive, and is even a less healthy alternative to cassava flour. We need to teach our people what they can do with local products, that they are not currently doing. A national farming system could turn every household into a unit of production, with excess supply purchased by the state, and processed into items with a long shelf-life. National education, through government media programming, could teach people how they can contribute, or how they can use items such as cassava flour.

What can we do to make life during the next pandemic more bearable? How can we act now, to not be like victims in the future? What must change? How can the Indigenous People of Trinidad & Tobago offer some vital guidance?

Trinidad’s Indigenous People are prepared to lead in establishing the foundations of a national cassava industry. We already have the support of the University of Trinidad and Tobago. The First Peoples Heritage Village, currently under construction, is well positioned to become the nucleus of an expanded agricultural enterprise—it will be a true model, to all other Trinidadians.

Notes

i “Indians” here as stated by the Authors, refer to the Amerindians, and not East Indians. From: Keegan, William. (1992). “Death Toll”. Archaeology (January/February), p. 55.

ii From: Ottley, C. Robert. (1955). An Account of Life in Spanish Trinidad (From 1498-b 1797). 1st ed. Diego Martin, Trinidad: C. R. Ottley, p. 42.

iii From Page 253 in: Joseph, E.L. (1970 [1838]). History of Trinidad. London: Frank Cass & Co., Ltd.

iv From: Goldwasser, Michele. (1994-96). “Remembrances of the Warao: the Miraculous Statue of Siparia, Trinidad”. Antropologica, p. 15.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 130–131.